About the Exam

The ABPN psychiatry exam is a marathon day-long computerized multiple-choice exam offered once a year with two dates in September. You can apply as early as November but the deadline is February (current dates here) through the “folio” website. You won’t schedule the actual exam until scheduling is opened, usually around 2 months before the exam dates. Results take around 8-10 weeks. In 2016, scores were released on November 30 (so 10 weeks).

Eligibility (see the info document):

- Graduate from a legit medical school

- Have a full medical license

- Finish residency (or be a senior on track to finish it before taking the test)

- Complete 3 Clinical Skills Evaluations (CSE)

Costs:

- $700 application fee when you register to tell them you’re ready

- $1685 examination fee when you schedule the exam with Pearson VUE.

You have 7 years after finishing your ACGME residency to pass the ABPN to become board certified. So you have plenty of tries if things go south (subsequent tries “only” cost the $1685 exam fee).

Exam & Content

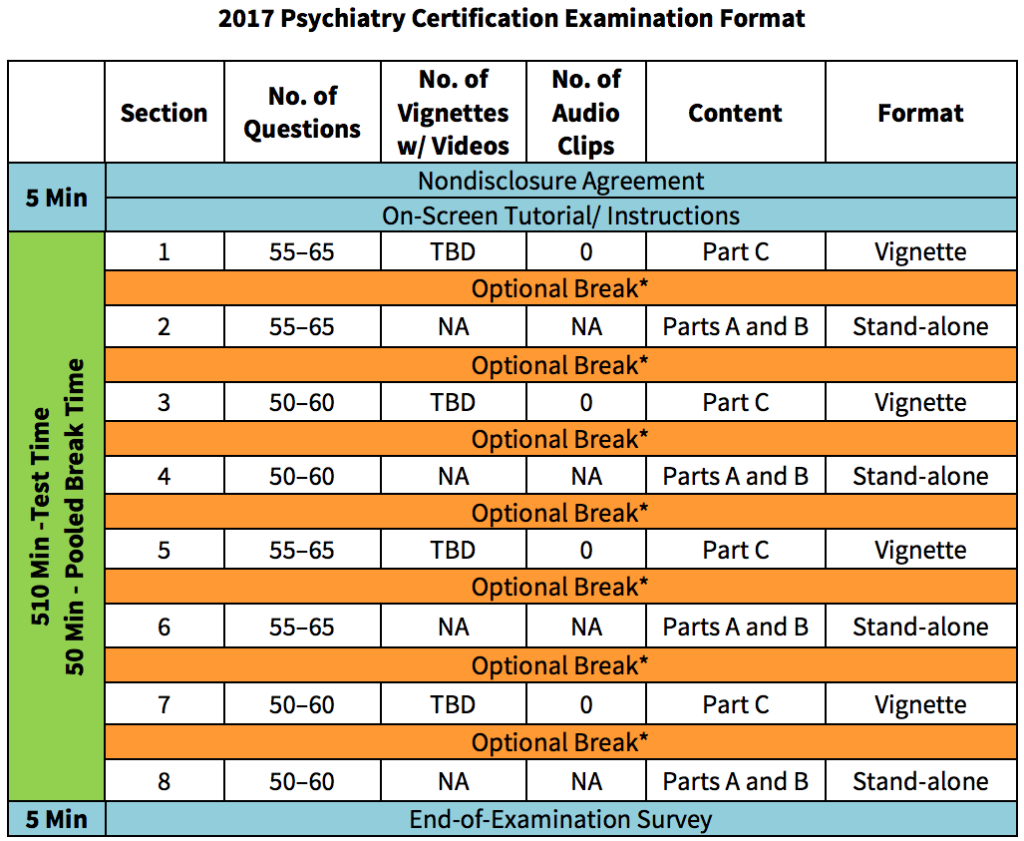

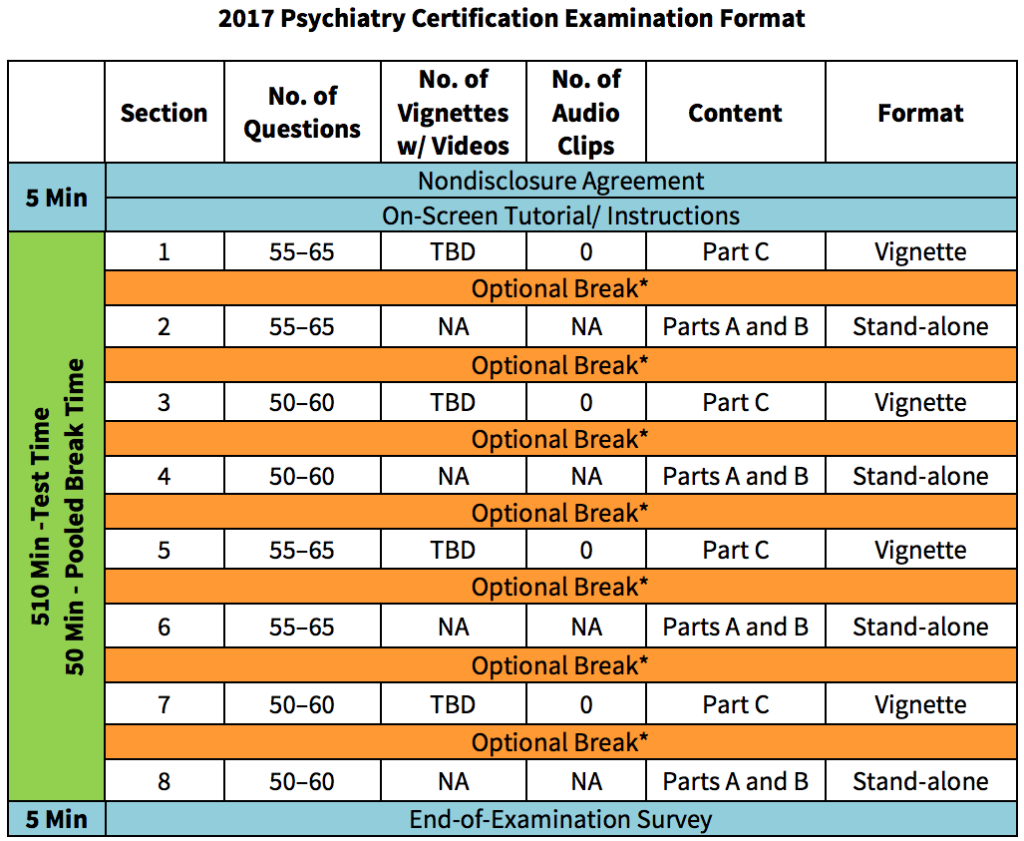

You get 50 minutes of break time that you can take between sections. Any breaks you take past the 50 minutes are permitted, but they then eat into your actual test time, which is 8.5 hours.

8 sections are split between Part A+B or Part C questions:

- 110 questions in Part A (Basic Concepts in Psychiatry)

- 110 questions in Part B (Neurology and Neurosciences)

- 230 questions in Part C (Clinical Psychiatry).

So 8 sections of 50-65 questions each for a total of 450 questions over 510 minutes. About 20% is neurology/neuroscience. Tack on a 5-minute intro and 5-minute post-test survey and 50 minutes break time, and the whole day can take up to 9.5 hours. 4 sections are vignette based and 4 sections are pure stand-alone questions (from the format and scoring document):

Stand-alone questions are one-best-answer multiple-choice questions that are not associated with any other questions. Part A and Part B questions are all stand-alone questions. For vignette questions, there are typically two to ten multiple-choice questions linked to a common case that may be presented in a video clip, which may vary in length from one to four minutes, an audio clip, or in a text vignette.

The ABPN does provide one sample video vignette to whet your appetite.

Historically, each Part was graded separately and needed to be passed. Now the test is graded in aggregate; it’s no longer possible to fail a single section and thus fail the exam. In 2016, a 71% correct overall was the passing threshold.

And everything is now DSM-V (from the policy document):

Starting in 2017, all specifications and content of all ABPN computer-delivered examinations will be based solely on DSM-5. No DSM-IV-TM classifications and diagnostic criteria will be applicable.

Board Books

Question Banks

Board Vitals

The most popular question bank for the ABPN is Board Vitals (which also has question banks for other specialties as well). This resource is definitely not error-free, and some users feel that it contains too much esoterica, but it’s still widely used. It’s $139 for a month. Using the code BW10 at checkout also gets you 10% off.

Overall, questions represent the board style pretty well, and the product is a good size (1639 questions). BV was completely updated to DSM-V in 2017. A lot of the “neuro” questions are actually psychiatry, so the neuro coverage is less than you’d guess from when you first log in. As an exclusively web-based product, there is no off-line access. You also need to hit the “show explanation” button to see the explanation for a question, which gets tiring after a while.

There is also a new optional 250 question package (actually 257) based on video vignettes available as an add-on (another $139/month), which is pricey but basically the only a la carte source for this question format currently.

TrueLearn

A new player is TrueLearn, which has products for both the PRITE and the ABPN ($25 off with that link). Questions overall feel harder and have a more basic science/med school type feel than those found in the other resources. The interface is a little more cluttered, but the software is overall solid: you can cross out answer choices and there’s also a “bottom line” summary statement, which is helpful.

Ultimately, TrueLearn is a reasonable second online question source after Board Vitals but overall probably not quite as high-yield yet. Overall, a couple of question sources are likely to be sufficient, so after Kenny & Spiegel and Board Vitals +/- more neuro review depending on your background, most test-takers are probably done question-wise.

Rosh Review

Rosh Review is the third of the big three online qbanks, and they offer a Pass Guarantee. 10% off their certification, child and adolescent, and PRITE products with code RoshPsych10.

Beat the Boards

Is a $1,097 online lecture course with a ~1000 questions and ~50 vignettes. We reached out to them to provide access for this review and were totally ignored. This is really expensive and ultimately unnecessary to pass.

Book round-out:

- Kaufman’s Clinical Neurology for Psychiatrists may be too long to read cover to cover during a limited post-work board review, but it also contains 2000 questions (extras are online) to help round out your neurology review.

- Psychiatry Board Review: Pearls of Wisdom is a change of pace written in a concise Q&A format which was useful as an adjunct, but it’s now a bit out of date and was neither as consistent nor as thorough as the other review books. It does contain a lot of high yield facts organized in a quick-read manner but is crying out for a DSM-V update.

- Unlike for Step 1, First Aid for the Psychiatry Boards isn’t the strongest source for psychiatry review and can be ignored. It purportedly does a passable job for neurology but remains a safe pass unless you just need to have another book.

Thanks to my awesome wife (the esteemed psychiatrist) for help in writing this post.