Another paper suggesting that clinicians prefer some structure (but not too much structure) in radiology reports. There are always edge cases where structured reporting becomes cumbersome–and overly parsed reports are also inefficient/unreadable–but there’s no denying it’s so much easier for me to scan a prior report when it’s not narrative free text.

A reader asked if anyone had successfully started a new radiology private practice recently, particularly one that involved financing, opening up new imaging centers, and fresh payor contracts. There is a vacuum in some areas, especially with the PE-exacerbated instability, and therefore a clear opportunity to those who can muster the manpower (no easy feat).

As a follow-up, I thought I’d ask (on their behalf): is anyone who has willing to mentor other upstarts?

In The Happiness Hypothesis, Jonathan Haidt describes work by William Damon at Stanford that sought “to see why some professions seemed healthy while others were growing sick”:

Picking the fields of genetics and journalism as case studies, they conducted dozens of interviews with people in each field. Their conclusion is as profound as it is simple: It’s a matter of alignment. When doing good (doing high-quality work that produces something of use to others) matches up with doing well (achieving wealth and professional advancement), a field is healthy.

In their study, modern journalists were suffering in the era of market consolidation and the growing attention economy:

Many journalists who worked for these empires confessed to having a sense of being forced to sell out and violate their own moral standards. Their world was unaligned, and they could not become vitally engaged in the larger but ignoble mission of gaining market share at any cost.

Contrast that with genetics, where doing good and doing well are usually the same thing.

Decide if you think being a healthcare worker in the now-typical corporatized environment reflects a coherent or incoherent profession. This is essentially the premise behind the “moral injury” reframing of physician burnout.

Unfortunately, recognition doesn’t really help because reclaiming coherence is hard:

A coherent profession, such as genetics, can get on with the business of genetics, while an incoherent profession, like journalism, spends a lot of time on self-analysis and self-criticism. Most people know there’s a problem, but they can’t agree on what to do about it.

The battle between Radiology Partners and UnitedHealthcare has ended with United as the victor.

The summary:

- RP claimed United owed them lots of money for underpayment because United was using a 2020 contract to determine some of its payments instead of a more lucrative 1998 contract originally held by one of its purchased groups, Singleton.

- United then sued Radiology Partners alleging an illegal pass-through billing scheme. It’s a good read.

- The arbitration panel awarded RP an interim award of $153 million. This was very much interim, not just because the independent panel had awkward bias conflicts, but also because the panel decided to separate the question of whether Singleton’s lucrative contract was in effect (it was) and if RP was abusing it (which it was) into separate steps.

The $153 million award would really have only been an extra $94 million since United had already paid for the work at a lower rate. (Author’s note: That’s quite the contract.)

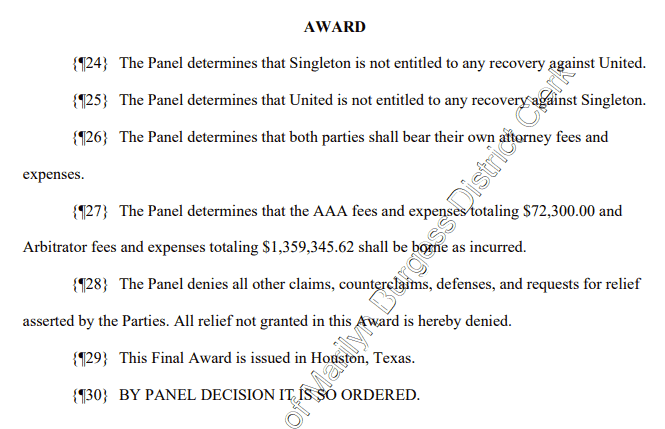

Phase III—that awkward fraud question—just finished. The ultimate findings of the panel (free login required):

In the Phase I Decision entered on April 2, 2023, the Panel made the following finding: “The Panel finds the 1998 contract to be the operative agreement between the parties.” The Panel confirms this finding.

In Phase II the Panel entered the Interim Award On Singleton’s Arbitration Demand on September 26, 2023. The Panel now vacates that Interim Award.

The difference between the amount United paid on claims pursuant to the rates specified in the 2020 Agreement and the amount it would have paid pursuant to the rates specified in the 1998 Agreement is $94,275,324.00. United’s underpayment of Singleton’s claims at the rate specified in the 2020 Agreement was a breach of the 1998 Agreement.

Because of its breaches of the 1998 Agreement and its other acts and omissions, Singleton is not entitled to recover this difference and underpayment or any other relief against United. Because of its breaches of the 1998 Agreement and its other acts and omissions, United is not entitled to any other relief against Singleton. The Panel determines that the evidence fully supports these decisions at law and in equity.

Translation: you are both jerks, you are both wrong in your typical unique and despicable ways, please go away forever:

United was wrong to unilaterally use the incorrect contract to determine payments. RP was wrong to hide its ownership and then essentially pretend that every group in the region it owns was Singleton when they clearly weren’t.

(For more description/backstory, see the previous two posts: United against Radiology Partners & United is Still Fighting Radiology Partners.)

For those keeping score at home, United’s lawyer was correct when they said, “We do not agree that Singleton will recover an award from UnitedHealthcare.”

In other news, whether or not they were right, United is still a terrible company.

Or, “Why Independent Radiology is different from most job boards (but also still boring)”

So recently I created a simple, small website called Independent Radiology. It’s a boring job board, but it’s also different from most job boards.

Jason Fried from 37signals (makers of Basecamp, HEY, and other stuff) argued years ago that software should be opinionated. A random WordPress website isn’t software per se, but I feel as a random dude on the internet with a full-time job, family, writing avocation, etc that anything extra worth doing in this sphere is only worth doing if it’s going to help someone and is unabashedly done the way I would do it. It’s a project that reflects my biases, preferences, and mission. It’s idiosyncratic. It’s opinionated.

The Context

When I first thought seriously about the issues with the ACR job board earlier this year that inspired this project (now significantly improved, you’re welcome), I was partly irritated by disingenuous job listings from Radiology Partners that were masquerading as independent private practices. But I was also struck by several things:

(more…)

The month of August has been almost exclusively related to the usual activities of daily living and the new/growing job board I’ve started dedicated to true independent physician-owned radiology private practices, which now has 45 groups. I know a service like Independent Radiology probably has more impact than my usual sporadic writing, but I’m personally looking forward to getting back to my usual idiosyncrasies in September.

Something happened to the field of Radiology.

Actually, a lot of things have happened and are happening to Radiology all the time, but one of those things has been that the proliferation of corporate and private equity-backed radiology practices over the past decade has been followed by a historic radiologist shortage, a subsequent piping-hot radiology job market, and a challenging zero-sum game to hire on-site and even remote radiologists.

There are thousands of rad jobs available in the country and more work than the field can handle, but only a fraction of those positions are at independent radiologist-owned and controlled private practices. A lot are not.

That’s why I’ve temporarily been posting a radiology job ad on this otherwise very personal site, and that’s why I’ve just launched Independent Radiology.

From the “Why?” page:

The thriving independent private practice of radiology is critical to the future of the field. True private practice–where doctors control the organization, are responsible to their peers and patients, and earn the full fruits of their labor–is the benchmark that sets the market and provides the anchor against exploitation from unscrupulous employers.

This site exists to help those radiologists looking for the real deal.

You don’t have to agree with me, and you also don’t have to care. Not everyone needs or wants to work in private practice, and of course that’s fine. I also believe in the academic mission, and there’s nothing inherently wrong with being an employee. I also don’t want to just glamorize a practice model. Models aren’t destiny, and a private practice isn’t necessarily a good practice.

But, I do believe every radiologist should hope for the success of independent radiologist-owned private practices. The ability to join a thriving independent practice where doctors get paid for the full amount of their professional work and have the autonomy to choose how to do it is what forces employers to compete. It’s the anchor. It’s the BATNA that every hospital and corporate suit knows you have. It’s what keeps them honest.

By another analogy, the employment model is the renting to a partnership’s buying. There’s nothing wrong with renting. Renting can be great! Sometimes, based on your finances, the available options, and the local factors, renting is simply a better, safer option than buying. It’s undeniable. Not every house is a good purchase. And, when you have a good landlord, who charges you a fair market rate and is quick to fix the things that break down, renting can be an easy low-friction experience.

But we are stronger as a field when ownership is a real possibility. And, like homeownership, when you buy a good property, in the long run, you generally end up ahead. You have to deal with some upfront costs and the upkeep—oh, the upkeep!—but you also have more say about the property and you’re not reliant on someone else’s goodwill or business savvy. You have a good place to live: a home, not just a house. For the renter, the landlord can always change. They can always call your bluff and see how far they can push you before you decide to move. That’s why viable options are important for the whole market.

So, I wanted to make some space online to help those who want to join and help build a practice to find what they’re looking for. And, I wanted to build a place to showcase true independent radiologist-owned private practices in order to help them find radiologists in this challenging market.

I hope it’s helpful.

More fun from Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. In case you missed it, we started with happy nihilism through cosmic insignificance theory and acknowledging the trap of productivity.

More on that inescapable finitude:

And it means standing firm in the face of FOMO, the “fear of missing out,” because you come to realize that missing out on something—indeed, on almost everything—is basically guaranteed.

That cuts.

Time pressure comes largely from forces outside ourselves: from a cutthroat economy; from the loss of the social safety nets and family networks that used to help ease the burdens of work and childcare; and from the sexist expectation that women must excel in their careers while assuming most of the responsibilities at home. None of that will be solved by self-help alone; as the journalist Anne Helen Petersen writes in a widely shared essay on millennial burnout, you can’t fix such problems “with vacation, or an adult coloring book, or ‘anxiety baking,’ or the Pomodoro Technique, or overnight fucking oats.”

So long as you continue to respond to impossible demands on your time by trying to persuade yourself that you might one day find some way to do the impossible, you’re implicitly collaborating with those demands. Whereas once you deeply grasp that they are impossible, you’ll be newly empowered to resist them, and to focus instead on building the most meaningful life you can, in whatever situation you’re in.

I do like overnight oats though.

The more efficient you get, the more you become “a limitless reservoir for other people’s expectations,” in the words of the management expert Jim Benson.

“A limitless reservoir for other people’s expectations” is a great line.

As she recalls in her memoir The Iceberg, the British sculptor Marion Coutts was taking her two-year-old son to his first day with a new caregiver when her husband, the art critic Tom Lubbock, came to find her to tell her about the malignant brain tumor from which he was to die within three years:

Something has happened. A piece of news. We have had a diagnosis that has the status of an event. The news makes a rupture with what went before: clean, complete and total, save in one respect. It seems that after the event, the decision we make is to remain. Our [family] unit stands … We learn something. We are mortal. You might say you know this but you don’t. The news falls neatly between one moment and another. You would not think there was a gap for such a thing … It is as if a new physical law has been described for us bespoke: absolute as all the others are, yet terrifyingly casual. It is a law of perception. It says, You will lose everything that catches your eye.

Which is a devastating way to come to the realization.

And, finally, most importantly, JOMO:

The exhilaration that sometimes arises when you grasp this truth about finitude has been called the “joy of missing out,” by way of a deliberate contrast with the idea of the “fear of missing out.” It is the thrilling recognition that you wouldn’t even really want to be able to do everything, since if you didn’t have to decide what to miss out on, your choices couldn’t truly mean anything. In this state of mind, you can embrace the fact that you’re forgoing certain pleasures, or neglecting certain obligations, because whatever you’ve decided to do instead—earn money to support your family, write your novel, bathe the toddler, pause on a hiking trail to watch a pale winter sun sink below the horizon at dusk—is how you’ve chosen to spend a portion of time that you never had any right to expect.

From Paul Graham’s “The Right Kind of Stubborn:”

The persistent are attached to the goal. The obstinate are attached to their ideas about how to reach it.

Worse still, that means they’ll tend to be attached to their first ideas about how to solve a problem, even though these are the least informed by the experience of working on it. So the obstinate aren’t merely attached to details, but disproportionately likely to be attached to wrong ones.

I like this distinction.

In some ways, Graham’s distinction between persistence and obstinance feels analogous to experts and “experts” (or, perhaps more fairly, between continuous growth and brittle skill).

There are people for whom expertise is partially a mindset: they question assumptions, their approach, and their knowledge. They want to be challenged, and they want to learn, and they want to improve.

And then there are those for whom expertise is a status. Their identity is tied to having the answers, and they know the right way to do things.

It’s a bit of a false dichotomy. People can be both obstinate and persistent in different contexts.

But if you’re overly rigid in your work or competing approaches feel like threats, you’re probably being too precious. Your excuse for doing things a certain way in the face of better alternatives probably shouldn’t be “It’s the way I learned how to do it,” or “That’s the way I’ve always done it.”

5 years into running a small one-physician psychiatry private practice, my wife’s EMR/EHR, Luminello, sold to private equity and was shut down to force its users to transfer to its new owner, SimplePractice. The whole experience was so shady that she was forced to survey the market and pick a new EHR. So she did.

(This post is mostly written by her in the first person. You also might enjoy our last post about how to start a psychiatry private practice.)