Luminello, my wife’s (now former) small practice EHR, just shut down, so I thought we’d end our sold-to-private-equity-just-to-be-shuttered-with-gusto story with a final litany of needless suffering and smarm.

Timing

To pressure people to switch to SimplePractice, busy psychiatrists running small private practices were given just two months before their current EHR shut down to research, pick, and migrate to a completely new platform. The plan for this acquisition was presumably always to shut the smaller company down and use its customers to gain a toehold in the physician market. Remove the time pressure so that people have the breathing room to look around, and you might lose some of the customers you bought.

Now technically the April 19th shutdown just was for solo practices. Group practices actually had longer to figure stuff out: until June 14. Haha wait just kidding SimplePractice just changed their mind: now it’s May 15.

Bulk Download

Luminello created a bulk download function to export charts as PDF files. The service intermittently worked and sometimes took over a week to generate the zip file. With that kind of uncertainty, some users felt compelled to request their downloads in advance to make sure they were ready to migrate to a new platform before the shutdown. Little did they know that Luminello would decide the feature was a one-time process and disable the button after using it. The patient care information generated while using the EHR after making the request wasn’t included, which would mean lots of manual document saving.

With enough complaining, you could get them to turn it back on.

Read-only

Luminello repeatedly advised users over and over that access would become “read-only” on April 19th and that no more changes could be made after that date.

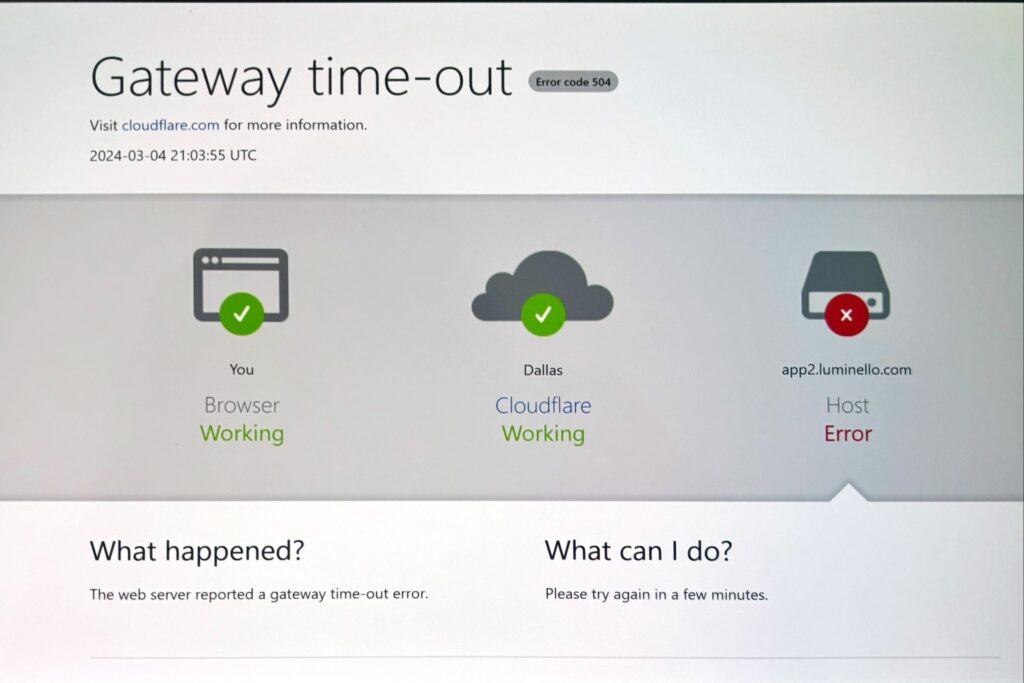

Instead, on April 19th, current users were greeted by only the magic bulk download button. You can’t actively look at the EHR contents, and anything not included in that bulk download (calendar, billing, etc) is totally unavailable. That is not what “read-only” means to literally anyone.

They quietly changed the language and now call it “export-only mode.”

People complained.

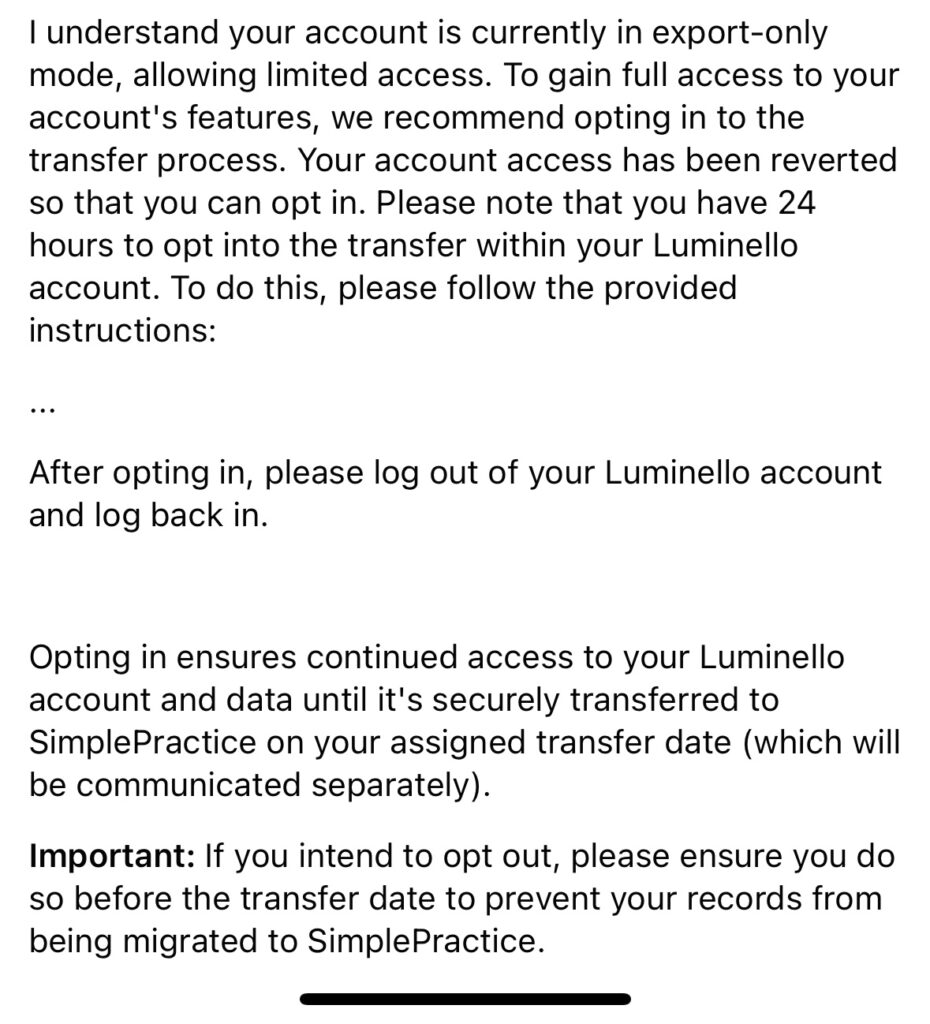

Users were told that they could have access reinstated if they opt-in to transfer to SimplePractice (and then opt out again before the assigned transfer date if they don’t want SimplePractice to have their data for no reason). An example:

Maybe a monthly fee or two for SimplePractice doesn’t seem like enough money for this to be worth it, so one possible explanation is that this last-minute rug-pull is to juice the opt-in numbers of switching customers so that the sale looks better. For what it’s worth, $3.6 million of the buyout was reportedly tied to post-sale metrics. One imagines this is one of them. Encouraging people to fake switch makes a lot more sense if there are a few million bucks in pending performance payments. (Note: What’s happening is what’s happening. Why it’s happening is just my guess.)

Billing

Last fall, after Luminello sold but while they were still maintaining that nothing was changing, they changed their billing plan from monthly to annual. My wife and many others paid for a full year. At some point later into that new payment term, SimplePractice announced that Luminello was shutting down. (They did eventually switch back to offering monthly billing before the announcement.)

They stated no refunds would be forthcoming.

After a lot of bitching online, Luminello agreed to refund people for the unused months of a product that was shuttered in the middle of a prepaid cycle. I’ll believe it when I see it.

But, for those on the re-instated monthly plan, Luminello has continued to freshly bill some customers after the service closed and entered read-only “export-only” mode. In addition to general incompetence, it’s hard to ignore the more cynical possibility that they assume a fraction of the overbilling will be overlooked or accepted because any customer service interaction or credit card dispute is a hassle that takes time.

Data Shenanigans

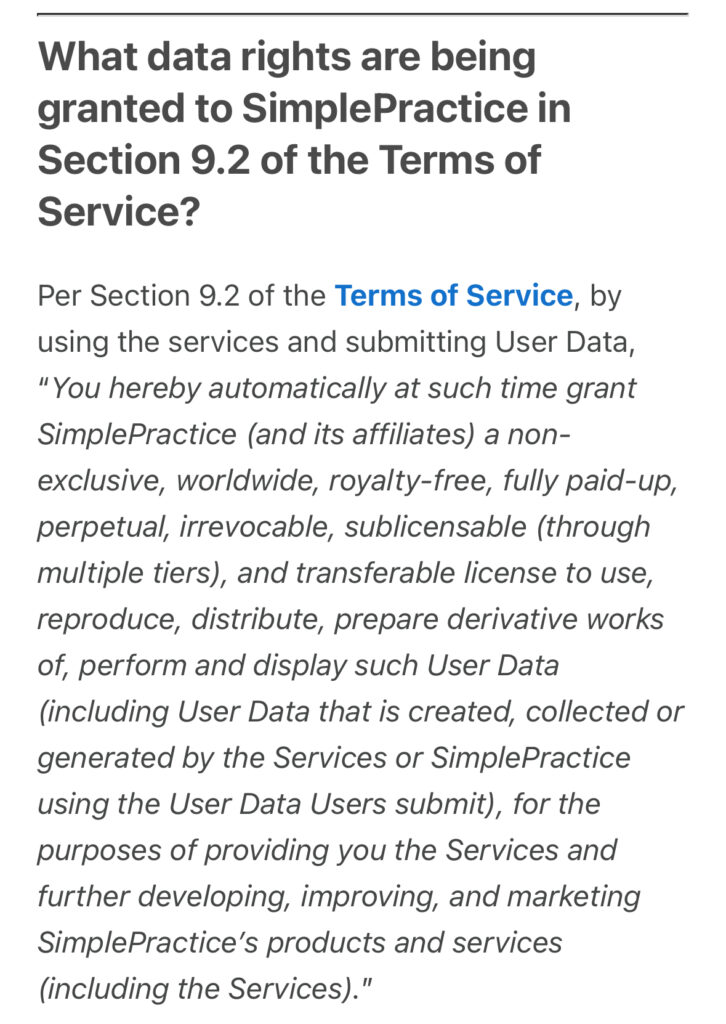

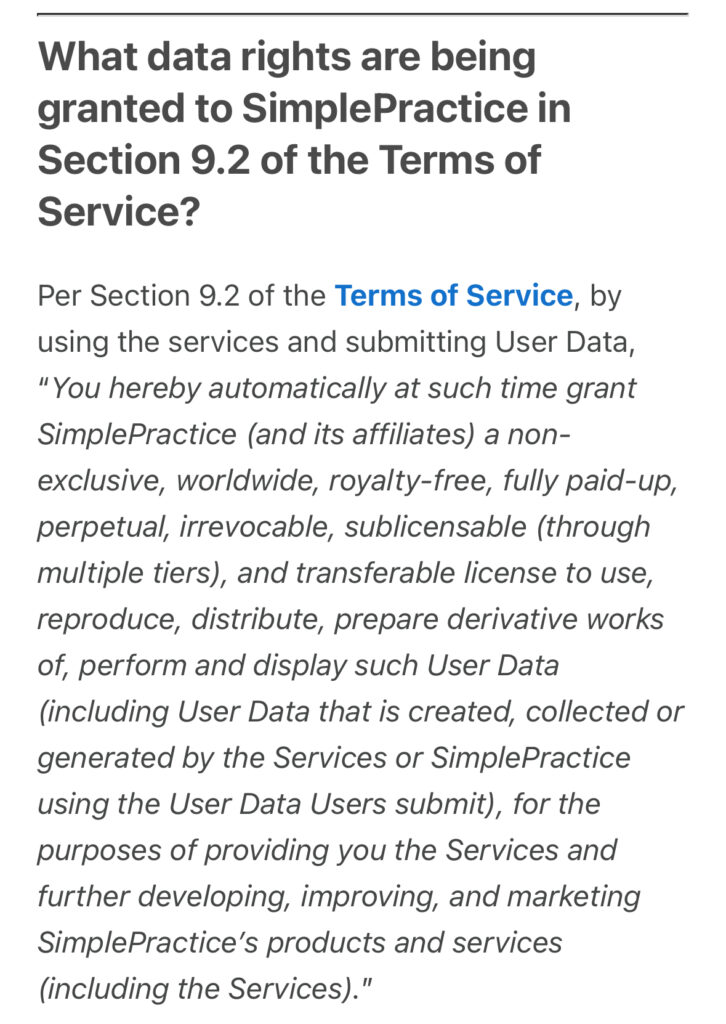

One of the fun things in SimplePracrice’s terms of service is that they want to play with your data:

Nevermind that the software you use for patient care has no business pretending to own people’s private health information or your practice’s work, but I personally find it offputting that they want to use everyone’s practice information for data mining and other sketchy stuff like some tech bro startup. I don’t think anybody wants their notes to be used without specific permission or compensation for training some AI tool (or anything else).

The Irony

The irony here is that by most accounts, SimplePractice is actually a decent product. It has a clean design and is—as promised—simple to use. While some of the physician features (better templates and dot phrases) are not fully baked and others don’t exist (lab/imaging order integration, flowsheets for vitals etc), the mission-critical ones like e-prescribe are now functional as promised.

If they had just waited a few months to actually have a physician ready EHR ready to demo and use before all this drama and communicated better, they would’ve had a higher sign on rate and fewer angry physicians.

And to their defense, this isn’t Vista Equity Partners Management’s first rodeo. I would guess that—despite a vocal contingent of very upset physicians—the majority of doctors took the path of least resistance and stayed with them as customers. Researching the EHR market and migrating to a new platform on short notice is really hard.

Reportedly, for many users, the migration process has been relatively smooth, even if customer service isn’t always helpful.

Everything I’ve described here and in the last post is entirely needless.

The foundational problem here is that there is a difference between having a good product and being a good company. What does it mean for healthcare if we keep rewarding the not-so-good companies?